The following is an excerpt from Ritual Magic for Conservative Christians. To read more, click this link.

“Theology, then, is fundamentally an attempt to make positive and constructive statements about who God is – and who we are in light of who God is.”

– Michael Jinkins

If the goal of this book is to bring an orthodox magic to Christians from as many denominational traditions as possible, then our first task must be in laying the groundwork for an ecumenical – that is, “across the board” – theology of magical Christianity.

This is no small task, as differences of almost every stripe exist across the denominational spectrum, ranging from Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy which are pretty much pre-packaged magical systems in a state of denial, to the Five-Point Calvinists and Rationalists who intentionally and methodically divorced every shred of spirituality from their religion.

On the one hand, our theology must take into account these denominational differences. On the other hand, our theology must accept that there are some groups – like the Jehovah’s Witnesses and Christian Scientists, for example – whose teaching is so far outside mainstream Christianity that they can’t be reconciled into even the most ecumenical of systems. This means we must focus on two points: those teachings that have the most support of history, and where there is the most common ground.

The Question of God

The point where all Christian theologies agree is the existence of one God, giving us our starting place. These theologies all agree that this God – variously called “Jehovah,” or “Yahweh,” or “Adonai,” or just simply “God” – is benevolent, all-powerful, and responsible for creating the entire universe.

Where these denominations begin to disagree is on who this God is. For example, most Christian groups believe God was pre-existing and pre-eternal, while Mormons believe God was once a human from a planet named Kolob, who eventually became God.1

Another point of disagreement is God’s number, which divides Christians into two camps:

Trinitarian – God is three Persons in one God: Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, or

Socinian – only God the Father is truly God; Jesus and the Holy Ghost are something other than God (Jehovah’s Witnesses identify Jesus with the Archangel Michael and the Holy Ghost with an impersonal force, for example.)

Our method is to ground our theology on historical precedent and on finding the most common ground, which in this case is the belief that God is pre-existing and pre-eternal, has always been God, and is composed of a Trinity of Persons with a Unity of Substance. This is the historical belief of Christianity as professed in her creeds and confessional formulas, the shared belief of Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, and every mainstream branch of Protestantism.

Jesus

We now come to the second Person of the Triune God, the person of Jesus; study of Jesus is technically called christology.

Christology was perhaps the single greatest cause for splits and arguments during the first five centuries of Christianity’s existence. Was Jesus God and man? Was Jesus merely a man? Was Jesus only God who made an appearance in human form. These controversies – Arianism, Docetism, Monophysitism and Nestorianism – raged through the Christian community like a storm and pitted brother against brother, sometimes to the point of violence. They were definitively settled at the Council of Chalcedon in 451, but have seen a resurgence in modern times.

Examples of this resurgence can be found in the Socinian camp, where Jehovah’s Witnesses teach Jesus was the Archangel Michael before being born on earth, or Christian Scientists who teach Jesus was merely a man able to manifest Truth. This is contrary to the historic mainstream teaching that Jesus Christ is fully God and fully man, the second Person of the Triune God, co-equal and co-eternal with God the Father and God the Holy Ghost.

This last teaching is the one we shall apply in our theology, again because it’s the most supported by the consistent teaching of history, and because it’s the unanimous teaching of Catholicism, Orthodoxy, and all mainstream branches of Protestantism.

The Holy Ghost

The Holy Ghost (or Holy Spirit) is the subject of pneumatology, which is less controversial than christology. The mainstream churches are agreed that the Holy Ghost is the Third Person of the Triune God, co-equal and co-eternal with the Father and the Son, the source of spiritual gifts and the Comforter.

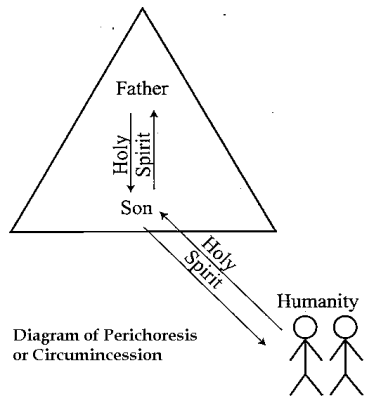

The general image of the relationship amongst the three Persons and the world is found in the doctrine of perichoresis or circumincession (also an agreed teaching), a process of kenosis or self-emptying: the Holy Ghost is the Father’s Love. The Father empties Love into the Son, who in turn empties that Love onto the earth. The Love (the Holy Ghost) encircles and fills the earth, to return to the Father and again repeat the process. The interaction between God and man can be seen in terms of that self-emptying.

The one major controversy over the Holy Ghost is between the Eastern and Western Churches: the Eastern Churches say the Holy Ghost proceeds from the Father alone, while the Western Churches say he proceeds from the Father and the Son.

It’s a complicated controversy that doesn’t concern our current project, and we needn’t take a position. My own thought runs as follows: the word we say as “proceeds” in the Nicene Creed is the Latin procedit, which in turn is a mistranslation of the Greek ekporevomenon which actually means “to originate, to be as from a source.” For our purposes it suffices to say no mainstream church teaches the Holy Ghost originates from the Son as well as the Father.

Human Free Will

The mainstream churches are rather unified when it comes to God as Trinity, yet they begin to fracture when it comes to the question of human free will. The question can be framed as: If God is truly sovereign over the universe, then are human beings really free or are their choices already made for them?

The answer runs a spectrum. At one end are Catholics and Arminians (the camp of most modern-day Evangelicals) who believe human will is completely free because God chose to allow it, while at the other end are five-point Calvinists who teach double predestination: i.e. that God chose from the beginning of time who would be allowed into heaven and who he would throw into hell.

To the Catholic and Arminian, man is free because God’s love wants a response made from love; to the Calvinist man is not free because if he were, then God would not be sovereign. In the middle of this spectrum are the Lutherans, who deny human will is perfectly free but teach single predestination: that God wills (i.e. predestines) everybody to get into heaven, yet the person’s choices can get him kicked out of that destination.

There’s a tendency to portray Calvinist teaching as a thoroughly pre-scripted universe (hence epithets like “the frozen chosen”), and I should point out that this is a misrepresentation. Rather, Calvin recognized two types of will: the will to make purely human decisions and the will to choose your salvation. His teaching, accurately represented, is that you’re free to choose your favorite TV show or your favorite flavor of ice cream, but you’re not free to choose a relationship with God or what’s ultimately happening to your soul.

While the mainstream churches are divided on this question, the historical teaching of Christianity is that human will is basically free, and the majority of churches tend to act as though the human will is at least partially free. In fact, the greatest common ground favors freedom of will, as true five-point Calvinists are in the minority. Thus our method squarely settles in favor of free will with the reservation that our choices can influence our salvation but we can’t decide it as though we had the final say.

Our First Major Conclusion

This brings us to our first theological conclusion: that the Triune God is all-powerful and the human person is free to enter into a loving relationship with this sovereign and all-powerful God. This is absolutely essential for our project because if any of these conditions is missing – God’s sovereignty, human free will, or the God-human relationship – then the concept of Christian magical practice becomes fiction.

Consider that it’s through God’s sovereignty that the universe is moved, and in free will that humans become participants in that movement. Through mutual love, God finds himself inclined to hear and care for the petitions of his human subjects, consequently moving the universe in the petitioners’ favor.

That relationship between human and God is of special concern to Christian theology, which sees that relationship perfected in the Second Person of the Holy Trinity: Jesus Christ. Christian orthodoxy teaches that Jesus is truly God and truly man, and became human so that humanity might be healed. While different denominations have different interpretations of how that healing actually happens (ransom? example? universal?), all mainstream Christians are agreed on who Jesus was and what Jesus came to do.

Grace

The word “grace” means favor, and almost all Christian denominations agree on three things: that grace flows to humanity by Jesus’ life, teaching, and death on the cross; that humans receive this grace by the working of the Holy Ghost (remember when we discussed perichoresis?); that the entire God-human relationship is based on God’s grace toward man.

Most denominations likewise agree that grace is “God’s underserved help,” and the distinctions arise when theologians try to analyze grace. While western theologians describe grace as a “gift,” eastern theologians describe grace as “God’s uncreated energy.” These two descriptions are not mutually exclusive, as “energy” comes from the Greek ενέργεια, meaning “working, operation, power in action.” Grace is indeed both: God’s gift of underserved help, and an example of God’s power in action.

Further debate occurs in the distinction between sanctifying grace and actual grace. The former is the grace that brings us to a state of salvation (sanctification), while the latter manifests as helps – such as prayers answered or fortuitous events occurring – the keep us in the faith and either obtain or maintain sanctification. The simplest description of the debate is that to a Calvinist, actual grace is an unnecessary distinction because the soul’s fate is predetermined.

I answer that there is only one grace, one power of God, and that the division into categories of “sanctifying” and “actual” is a human attempt to understand the different purposes to which God’s grace is directed.

Channels of Grace

“We thank thee for the Holy Ghost, the Comforter; for thy holy Church, for the Means of Grace, for the lives of all faithful and godly men, and for the hope of the life to come”

– prayer from the Lutheran Service Book and Hymnal

We’ve established that grace is divine gift, divine power, and divine energy. Likewise we’ve suggested in passing that grace, as a product of God’s love, is distributed to humankind by the workings of God’s Love (God the Holy Ghost) enfolding, encircling, and penetrating the universe by way of perichoresis or circumincession. We can also safely say that actual grace is analogous to what magicians commonly call “energy.”

As we’re not merely building a systematic theology but instead discussing a theology of magic, it becomes imperative to determine how that grace is channeled from the Triune God’s circumincession through all creation and into our day-to-day lives.

1. Prayer

All denominations are agreed on the effectiveness of prayer. Prayer is effectively the conscious and deliberate appeal to the God-human relationship with the purpose of manifesting further grace in the petitioner’s direction.

Unanimous agreement also holds that prayer can be vocal or mental, that is with one’s words or with one’s thoughts alone. The basis of this teaching is that God knows our thoughts as well as our words, and thus is able to respond accordingly.

2. The Scriptures

Another universally-agreed channel of grace is the Scriptures. While the Bible itself has no inherent energy or miraculous properties, it’s considered to be a channel of grace because it contains all the information required for salvation (i.e. sanctifying grace). Therefore it can be said to channel a grace of spiritual knowledge.

3. The Sacraments

Distinctions start to show when we move to the next channel of grace, the sacraments. The consistent teaching of Christian history and the numerical majority of modern Christians (Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Lutherans, and Anglicans) are agreed that a sacrament is “a visible sign of an invisible grace,” a channel through which God’s grace is manifest to the faithful. While there is disagreement on the number of sacraments and what they actually do, the general agreement is that the sacraments “work” somehow.

The opposite opinion (Reformed and Anabaptist) is founded in Ulrich Zwingli’s assertion that the sacraments weren’t given as God’s way to help us, but are merely symbolic ordinances by which we show our faith to God and to the Christian community. This is a bitter debate that rages in some quarters even today, yet fortunately this isn’t a book on sacramental theology. While a Catholic or a Protestant theology of magic will come to different conclusions on their own, all agree that God also gives grace outside the sacraments. Therefore an Ecumenical theology of magic can afford to be content with encouraging people to gather around their own conclusions.

4. The Sacramentals

Sacramentals are a second-cousin to the sacraments, and are spiritual helps for receiving actual grace in one’s life. Examples of sacramentals include blessings, exorcisms, medals, scapulars, holy water, the sign of the cross, and prayer. The term itself is almost exclusive to Catholic theology, but the concept – any action that helps manifest actual grace – is more ecumenical in its scope and appreciation. A theology of magic would categorize magic as a sacramental.

5. Morally Upright Living

In modern western religious language, the word “morality” has become synonymous with “sexual repression.” That’s not how I mean it here.

The word “morals” comes from the Latin mores, which at it root means “custom” or “prescribed behavior.” In its best form, behavior that’s “prescribed” – such as don’t lie, don’t kill, don’t steal, and so on – is prescribed on the basis of being in the best interests of the individual as well as for society.

Anthropologically, we can see the energy and the charismatic appeal of a person who deals fairly and honestly with others, not because it’s expected of him but because that’s who he is. When we do “the right thing” out of some hope of heaven or fear of hell, when we do it without our heart really being in it and for the benefit it brings others as well as ourselves, that’s when being “moral” can become soul-crushing; we ourselves become weak and crushed.

Theologically there’s unanimous agreement that some connection between moral conduct and grace exists, yet bitter debate over how that relationship should be understood. Generally Catholics believe that grace comes from faith and works (moral actions), while Protestants believe that works are merely the fruits of a lively faith and that grace results from faith alone (sola fide); many intermediate positions exist with that spectrum.

Our theology can be content with the conclusion that a relationship between actual grace and moral living exists, without quibbling over the details of how. We can let the theology professors argue that to their heart’s content while we happily move forward.

Our Second Major Conclusion

Our theology has just gained a grasp for what grace is, where it comes from, and how we can receive it. In short, grace is the gift of God’s uncreated energy. It is a product of God’s love and this energy permeates the universe through the workings of the Holy Ghost proceeding through creation.

Not only does this grace exist, this grace is available to us through several channels: prayer, the Scriptures, the Sacraments, the sacramentals, and upright moral conduct. It is through one of these channels, prayer, where we are able to call upon and direct this energy in the form of actual grace manifesting our desires.

Prayer can be mental (thought, meditation, visualization) or vocal (speech in one’s own words or according to prescribed formulae), and the energy of actual grace can be used and – as the existence of “dark” magicians demonstrates – abused. In fact baneful magic can be considered sinful because it’s the abuse of a God-given gift.

We have already defined magic as applied theology, and as such our theology considers magic the process of working with and manifesting this divine energy in our lives.

The Spiritual Hierarchies

Theological investigation also finds another point of agreement among Christians: that God is attended by a host of spirits who assist man from time to time; the Bible calls these spirits “Sons of God” or “Angels,” and hints that these Angels exist in hierarchies; extra-biblical texts show that this was indeed the belief of Old Testament-era Judaism. Thus in addition to God’s power and love for humanity, he has created legions of spirits who assist us.

So far there’s no disagreement. The disagreement comes, as in all issues, regarding the manner of that assistance. For example, can we call upon an angel to help us, or is it something God commands with no consideration or input from his human subjects?

The denominations are hotly contested over this question, with Catholics and Eastern Orthodox firmly on the side that we can call the Angels (and the Saints) as spiritual helpers, with the Reformed claiming such a thing is idolatry and superstition. In the middle we have the Lutheran position which concedes the Angels and Saints intercede for us constantly but that “invocation, though harmless, is unnecessary.”

The consistent teaching throughout Christianity’s history is that we can call upon the Angels for help and numerically this is the majority position; hence it will be the position taken by our theology. As to the matter of prayer to the Saints, we may advocate for it but are content to leave it an open question.

The Final Product

“I can write no more. All that I have written seems like straw.”

– St. Thomas Aquinas

This is the theological foundation on which we can build an ecumenical Christian magical paradigm: God’s power, human free will, the possibility for a loving relationship between God and us, the ability to channel God’s power, and the spiritual helpers God has assigned to us.

This theology is incomplete in areas that don’t directly affect magical practice: soteriology, eschatology, sacramentology, and moral theology, to name a few. Yet it does not need to be complete; we seek only to establish a theological system of magic that can cut across and be viewed kindly by the largest number of people from the largest number of denominations, and in this I pray we’ve succeeded.

Let’s move in from this section, then, as we continue the next steps on our magical journey!

Notes for Chapter One

- This teaching is taken from Joseph Smith’s King Follett Discourse, 1844.

This blog post was an excerpt from Ritual Magic for Conservative Christians. To read more, click this link.

I was raised Jehovah’s Witness, and am not now a Christian. But this is fascinating and very precise. I appreciate the amount of research and thought that went into this post/book, and I think it will have a wide appeal.

LikeLike

Pingback: Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram: Thoughts and Theology | THAVMA: Christian Occultism and Magic

Pingback: Energy Flow and the Latin Mass | THAVMA: Christian Occultism and Magic

I wonder about saying that prayers can actualize our desires and direct energy. Are they not only petitions?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi there! When we say “only petitions,” we’re reducing to the verbal content of prayer while not addressing the mental and corporeal aspects. The way I see it, prayer is anything that sends a message to God, meaning everything we think, say, and do (i.e. our entire life is a prayer be it for good or ill).

Combined with the teaching that God assists in every act of His creatures (found in Jerome, Augustine, Section I,2,22 of the Tridentine Catechism, and treated more fully on page 88 of Ott’s Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma), this makes our entire life a direct participation in God’s energies whether we’re conscious of it or not. This brings us to Jesus saying “Knock and the door shall be opened,” and the saying in James that “the prayer of the just availeth much.” For me, this plus experience convince me of prayer’s ability to manifest our desires.

LikeLike