Or, the blog post where we explore the question I started asking 24 years ago. And likely alienate all our readers in the process . . .

If you wish to “get to the point,” please skip to “The Bottom of the Rabbit Hole.” This blog post is long and spends 50+ pages setting up context, which I feel is important but not every reader will need to the same degree. So feel free to start there and read backwards as you deem useful, desired, or necessary.

Table of Contents

1. Obligatory Disclaimers and Expectation Management

2. Acknowledgements and Special Thanks

3. Preliminary Considerations

– Definition(s) of Ordination

– The Evolving Understanding of Holy Orders

– Alternate Spiritual Currents, Gendered Lineages, and Esoteric Transmission

– Outlier Situations: Women Ordained by Mainstream Bishops

– Differing Levels of Intellectual Honesty

4. Origins and Function of the Diaconissate

– The Diaconate in General: Origins and Intended Function

– Did the Apostles Ordain a Sacramental Diaconate?

– The Female Diaconate

– Was the Diaconissate Sacramental?

5. Church Councils and the Diaconissate

– Ecumenical: First Council of Nicaea (325)

– Regional: Synod of Laodicea (372)

– Regional: First Synod of Nimes (396)

– Regional: First Synod of Orange (441)

– Ecumenical: Council of Chalcedon (451)

– Regional: Synod of Epaone (517)

– Regional: Second Synod of Orleans (533)

– Regional (Eastern): Quinsext Synod in Trullo (692)

– Regional: Sixth Synod of Paris (829)

– After the Councils

6. Certain Arguments I Find Unconvincing

– Pro: “There Was a Break in the Understanding of Holy Orders”

– Con: “Jesus Clearly Intended for the Clergy to Be Male”

– Pro: “We Can Prove the Early Church Had Women Priests and Bishops!”

– Con: “Women Have Never Been Ordained in the Church’s History”

– Pro: “The Words Benedicere, Consecrare, and Ordinare Used to Mean the Same Thing”

– Con: “We Have to Judge Historical Questions According to the Current Teaching of the Magisterium”

– Pro: “You’re a Misogynist if You Disagree with Even a Little of What I Tell You!”

– Con: “Shut Your Brain and Kowtow to What the Magisterium Tells You!”

– Both: “Who Are You to Disagree with Me? I Have a Ph.D. in So-and-So!”

– What Else?

7. Finally, we Have Our Context!

8. The Bottom of the Rabbit Hole

– Unanswerable

– Irrelevant

– This Is Why There’s Always “Something Else”

– What Would a Female-Lineage Christian Priesthood Look Like?

– Pastoral Considerations

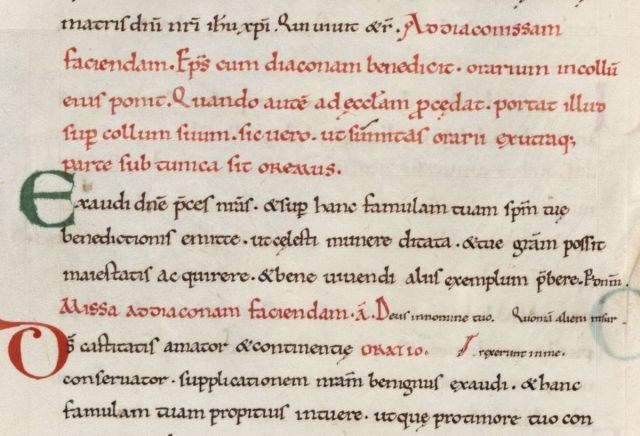

Appendix A: Order for Making a [Female] Deacon

– Commentary

– Translation of the Ritual Text

Appendix B: Ordination of an Abbess, Text #1

– Commentary

– Translation of the Ritual Text

Appendix C: Ordination of an Abbess, Text #2

– Commentary

– Translation of the Ritual Text

Appendix D: Benediction of an Abbess from the Roman Pontifical

– Commentary

– Translation of the Text

Prologue

New information demands new conclusions.

For over 24 years, I have asked myself the question “what is the real reason a woman can’t be ordained?”

When that question first occurred to me, I was still attending Holy Family (the indult community in Dayton), and one of my friends on the choir, Steve, was an ex-seminarian. So I asked him the question. His answer was unsatisfactory, along the lines of: “St. Paul says women shouldn’t speak in the churches or have authority over a man.”

That answer wasn’t satisfactory, and I countered by saying, “That was just Paul giving his personal opinion. What else do you have?”

“Well, Jason, you just have to obey the Magisterium.”

To which I say, “I hope you THAVMA readers know me better than that!”

Ever since that day, I had been unable to find a satisfactory answer. This includes engaging with both sides and either being told by one side that I’m either “misogynist” or “regressive” for not marching in lockstep, or being told by the other side that “all theology is based on authority” and that I’d better toe the line.

So, as I wrote 13 years ago, I’m still on the fence from the perspective of theology alone, because the only question I need to have answered remains, well, unanswered. It doesn’t help that big-T Tradition offers nothing but silence, and nobody on either side is able to admit the question even exists. I guess they see no sense in letting the Deposit of Faith get in the way of their agendas!

To summarize, these have been my positions for the past 24 years:

One: Women have not (traditionally) been sacramentally-ordained in the history of the mainstream Orthodox and Catholic ordinal lineages, though “outliers” are known.

Two: This does not mean a woman cannot be ordained in these lineages.

Three: The only way to determine whether a woman can, is to find out whether the sacramental character of Order can be imprinted onto a woman’s soul.

Four: For whatever reason, Sacred Tradition has never bothered to deal seriously with the latter question, and formal theology similarly lacks both the deep-level conceptualization and the vocabulary for addressing the mechanics of the spiritual principles behind how the sacraments operate.

Five: This silence from Sacred Tradition leaves us an open question that cannot be sufficiently answered from Public Revelation alone.

Six: Any conclusion reached thus necessarily errs on the side of caution or on the side of presumption, and

Seven: I choose to respect others’ conclusions, so long as they’re willing to respect mine.

I repeat: new evidence demands new conclusions. And I have discovered much that was unknown to me when I wrote 13 years ago. My Latin is much better now. I’ve since learned to read paleography. More source-texts are available to the average person than at any time in history. I have encountered female clergy who, if they were male, would’ve been considered excellent candidates for ordination in the “regular church.” And perhaps most importantly, being 15 years removed from the Traditional movement has given me room to overcome many of my previous intellectual biases.

The new evidence I found – at least it was new to me – came in the form of several diaconissal and abbatissal ordination rites dating from between 650 and 1200, along with the decrees of local councils dating between 396 and 829. This threw me down a very deep rabbit hole finding text after text, some of which turned my worldview upside-down.

Obligatory Disclaimers and Expectation Management

As we begin, I feel it necessary to make a few things clear. Perhaps more clear than anything else I’ve written,

I write this neither as enemy nor ally. I am a centrist who intends neither to champion women’s ordination, nor to attack those churches who practice it. I see most people on both sides as having a legitimate disagreement and doing the best they can with the information they have, and believe there is room for difference of opinion. For reasons I intend to explain, I just don’t trust either side’s thought-leaders and find both sets of arguments unconvincing.

Likewise, I am only talking about this question in context of the Roman Catholic Church and those churches who retain the Roman Catholic doctrine of an indelible sacramental character. Everybody else can pretty much solve the question by reading Galatians 3 or appealing to their denomination’s historical practice. I may draw from other churches in order to present examples, but nothing I say here is intended to apply to Eastern Orthodox, Protestants, Ecclesiastical Gnostics, or anyone else unless I explicitly name them.

This blog gets its fair share of hate-readers who like to quote-mine. So let me be very clear about this too: I am neither condemning or endorsing any person or group under discussion. If I give a sympathetic treatment to a person, group, or subject you don’t like, that’s because I’m endeavoring to treat everyone sympathetically. That includes those with whom I disagree virulently. If you can’t handle that, you don’t have to keep reading.

First Principles. My theological orientation is generally traditional, albeit my method is more influenced by the Wesleyan Quadrilateral than I’m supposed to admit out loud. My intellectual orientation tends toward skepticism and empiricism. I believe objective truth exists, and I believe the human mind is capable of knowing objective reality. I value results over theory. I am profoundly disinterested in philosophy, particularly Continental philosophy which I liken to mental masturbation. These are my First Principles. If your First Principles are different from mine, then it’s only logical that your conclusions will be different from mine. The universe is big enough for both of us, so you do you.

I am Libertarian. I believe other people are not my property, and certainly not the property of any “collective.” I have no use for the Leftist or Rightist ideologies driving either side of the debate, and reject all forms of Collectivism, Identitarianism, Legal Positivism, and Authoritarianism as a matter of principle.

I will not be addressing the real or imagined issues Traditional Catholics raise against the 1552 and 1968 Ordinals. My position is that any potential defect in the 1552 Ordinal was most likely corrected in the years between 1930 and 1970. The debate over the 1968 Ordinal is an internal matter within the Traditional Roman Catholic movement, and I find the arguments against its validity based on an overly rigid view of what constitutes an essential sacramental form (and in the case of some individual critics, an outright wrong view).

This discussion is strictly hypothetical. Talking is not the same thing as doing, a distinction that seems lost on a lot of people. The way I see it is that one can talk in hypotheticals about anything they want, but they’re not really taking a side until they actually do something that requires them to commit. In my situation that translates as follows: I can talk about either side of women’s ordination all I want, but I would only be picking a side if the day comes that I lay hands on a woman’s head with the intention of cheirotonia.

Last but not least: this is only a blog post, not doctorate-level research. My use of “semi-colloquial” language is intentional. I make no pretense at being an expert on the topic, and I certainly don’t expect to end a 370-year long debate by scribbling on the internet! I’m just someone with unanswered doubts who distrusts both sides of the debate, and am only sharing what I found on the course of this intellectual journey.

I do, however, hope this will the last thing I have to say on the subject for at least the next 10 years …

Acknowledgements and Special Thanks

Several people have given feedback on snippets I’ve posted for review on social media, and they’ve helped this blog post become better because of it. Others have had blogs (active or defunct) that I’ve referenced or quoted, and still others have had conversations with me that forced me to do some thinking. They all have my utmost gratitude:

I’d like to take a moment to thank Jenny Tyson, Kristopher Manghera, Fork Nan Pwen bon houngan, John Plummer, David Oliver Kling, Bartimaeus Black, Kathy Cason, and all others who’ve contributed to this whether through DMs, comments, E-mails, and every other form of feedback.

In different times and in different ways, every last one of you has caused me to think in different directions even if you didn’t realize it at the time. There’s a strong chance I didn’t realize it either!

One final acknowledgement: All Biblical quotations are from the Douay-Challoner Bible. All other translation work is my own unless otherwise specified. I have striven for formal fidelity but have not shied away from dynamic translation in those places where it would make for a more natural English reading.

Preliminary Considerations

This article will be something of a follow-up and expansion on my article about the women’s ordination debate written in 2010 and slightly updated in 2016, largely because new information leads to new conclusions. Since the topic itself is complicated owing to a number of historical and theological factors, I’d like to start by giving some context for the various source texts as well as any conclusions I draw from them.

This of course raises an important point: reading a source is one thing, but understanding a source is quite another. It is important to read each source in context, otherwise we end up like so many people who misquote the Bible. I will endeavor to keep all sources in context while making no claim my conclusions represent objective truth. My only claim is that I shall do my best to get as close to truth as my information and understanding will allow, and that I will strive for my conclusions to follow logically from my premises.

Definition(s) of Ordination

Perhaps a good place to begin is by discussing the definition(s) of the word “ordination.” To most Catholics this word simply means “the rite that makes a man a bishop, a priest, or a deacon.” Yet the word had a much broader use in ancient times.

Since the word “ordination” derives from the word “order,” we can work our way backward from there. Among the ancient Romans, an “order” referred to “an established civil body,” and commonly refered to one’s rank in society. A more modern term for this usage of the word “order” would be “class” in general and either “social class” or “professional class” in particular. This was contrasted with the “plebs,” which referred to the common people in general.

So in this first sense, “ordination” or “ordering” means to set someone apart from the “regular people,” and assigning them a rank within the social or professional order.

This forms the foundation for the term when it was imported into Christian parlance, where it came to mean “setting a person apart into a rank within ecclesiastical society,” while believers outside these orders came to be referred to in Latin as laici, derived from Greek ὁ λαός (“o laós”), referring to “the people;” this is the root of our English word “laity.” Hence the institution of orders and laity can be considered a copy of the social order in which the early Christians lived, and was marked by the laying-on of hands accompanied with prayer (see Acts 6:6 and 1 Timothy 4:14).

In this second sense, ordination means to set a Christian believer apart from the “regular people,” assigning them a rank within the ecclesiastical order by a rite involving the laying-on of hands and prayer.

The word came to be more restricted still. As early as the Apostolic Tradition attributed to Hippolytus (c. 225 AD), we see the word “ordination” restricted to those with liturgical duties, shifting away from the Roman concept of Order:

The widow shall be appointed by the word alone, and [so] she shall be associated with the other widows; hands shall not be laid upon her because she does not offer the oblation nor has she a sacred ministry [alternate reading: “nor does she conduct liturgia”]. Ordination is for the clergy on account of their ministry, but the widow is appointed for prayer, and prayer is the duty of all.

[Source]

In this third sense, ordination means to set a Christian believer apart from the “regular people,” and assigning them a rank associated with liturgical functions, by a rite involving the laying-on of hands and prayer.

Our progression now meets with the “Augustinian Doctrine” upheld by the Western Church. Ordination came to be seen as imparting an indelible mark upon the soul of the person being ordained. This indelible mark, technically called a sacramental character, is considered the source of the cleric’s spiritual powers (e.g. the power to offer the Eucharist), and cannot be taken away or surrendered, even if the individual cleric were to fall into heresy, schism, or outright apostasy. This is first spelled out in St. Augustine’s Against the Epistle of Parmenianus where he makes clear the sacrament of Ordination cannot be lost, and that “the Sacraments are everywhere.” He uses the conversion of heretical clergy as an example:

For that which certain people have begun to say with a conviction of truth, “One who leaves the Church does not lose his Baptism, but loses the right to administer it;” appears, by many ways, to be said inanely and in vain. Firstly, because no cause is shown: why he who cannot lose his own Baptism would be able to lose the right to administer it. For either is a Sacrament, and either is given to a man by way of a certain consecration; this when he is baptized, that when he is ordained. And therefore it is not allowed to be repeated within Catholicism. Now also, when the clergy convert [lit. “leaders come over from that party”], for the benefit of peace they are received and converted from the error of schism, and if a need is seen that they bear the same office they bore [with the other sect], they are not re-ordained. Rather, as their Baptism remains intact, so too does their Ordination; because as the vice was corrected by way of their conversion [lit. “cutting off” (from the other sect)] for the peace of unity, but not in the Sacraments, which are everywhere.

(Translated from Book II, section 28; emphasis mine)

Augustine’s main point is explaining that heretics also possess valid Sacraments, and how such a thing can be so. In the next section Augustine gives his thesis a finer point, using the example of a layperson who administers baptism and ending with the metaphor of the mark of the Legions imprinted on the body of someone who has never fought before. I quote the relevant sections. (Book II, Section 29, ellipses used for the sake of brevity):

However, if some layman was compelled by necessity to give [Baptism] to a person on their deathbed (because he learned how to give it when he himself received it), I don’t know who rightly says it needs to be repeated. Even if he does so without being driven by necessity, it is a usurpation of another person’s job … If it is usurped and there is no necessity, and [Baptism] is given by anyone to anyone, what has been given cannot be said not to have been given, even though it can be rightly called illicit … nevertheless it shall not be considered as not being given.

Nor by any means does a devoted soldier disrespect the Imperial insignia when it has been usurped by private individuals. For if someone secretly goes outside the law, and in the public mints, beats and puts a seal on gold, silver, or brass; … if the Imperial seal has been recognized, are the coins not piled into the Imperial treasury?

Or if anyone, whether a deserter or someone who has never served, were to brand the mark of a soldier onto some private individual; were it not so that (when apprehended) he is punished as a deserter? … Or if this non-soldier trembles with fear from the soldier’s mark upon his body and flies to the Emperor’s mercy, and begins to serve after having gained that forgiveness by pleading and effusive prayer; surely the mark is not re-given to the man after he has been freed and corrected, but the old mark is recognized and approved!

Do the Christian Sacraments adhere less strongly than this bodily mark? When we see that the apostates do not lack Baptism, and in any case it is not repeated over them when they come back [to the Church] through penance, and therefore is it not the judgment that they could not have lost it?

I quoted so much of this section because it is important for understanding Augustine’e point. St. Thomas Aquinas elaborates on the permanency of the character in the Summa Theologiæ (III, 63, 5):

As stated above, in a sacramental character Christ’s faithful have a share in His Priesthood; … Now Christ’s Priesthood is eternal, according to Psalm 109:4: “Thou art a priest for ever, according to the order of Melchisedech.” Consequently, every sanctification wrought by His Priesthood is perpetual, enduring as long as the thing sanctified endures. … Since, therefore, the subject of a character is the soul as to its intellective part, where faith resides, as stated above (Article 4, Reply to Objection 3); it is clear that, the intellect being perpetual and incorruptible, a character cannot be blotted out from the soul.

Finally – and the reason I spent so long developing this section – this is the official Roman Catholic teaching. Its official expression was given at the Council of Trent. Canon 13 of the 7th Session tells us that “If any one saith, that the received and approved rites of the Catholic Church, wont to be used in the solemn administration of the sacraments, may be contemned, or without sin be omitted at pleasure by the ministers, or be changed, by every pastor of the churches, into other new ones; let him be anathema,” while Canon 3 of the 23rd Session anathematizes anyone who claims “that he who has once been a priest, can again become a layman.”

It should be stressed that Augustine was not inventing a novel doctrine, so much as describing the concept of the “seal” present in the New Testament discussion of Baptism, Confirmation, and Ordination. When St. Paul discusses this seal, he uses variations of the word σφραγίς (“sfra-yís”), which could refer to a seal, a signet ring, or the impression stamped by that ring. This word survives in modern Greek as σφραγίδα (“sfra-yí-dha”), where it refers to “an indentation or imprint made by stamping.” We see this clearly in 2 Corinthians 1:22, where Paul refers to us as “Christ also hath sealed (Gr. Σφραγισάμενος) us, and given the pledge of the Spirit in our hearts.”

We see variations of this word in Ephesians 1:13, where Paul refers to the community as “signed (Gr. ἐσφραγίσθητε) with the holy Spirit of promise,” and the same word again in Ephesians 4:30: “And grieve not the holy Spirit of God: whereby you are sealed (Gr. ἐσφραγίσθητε) unto the day of redemption.” (One possible reading of this last verse is to imply a lifelong duration of the seal.)

In Apocalypse 9:4 we read of those “who have not the sign (Gr. σφραγίδα) of God on their foreheads.” (Notice this is the same form of the word that survived into Modern Greek.)

The seal is discussed in patristic literature, and directly referenced in the Eastern Orthodox and Novus Ordo rites for Confirmation, both of which invoke “the seal of the Holy Ghost” upon the confirmand. Augustine, therefore, is simply one voice in a long tradition attempting to explain the Church’s understanding of St. Paul’s word σφραγίς, both in and of itself and in conection with the Church’s practice of not re-baptizing or re-ordaining people who were either baptized or ordained outside the Catholic Church, and defining the Catholic position vis-à-vis the Donatists regarding those who chose to burn that grain of incense during the persecutions because staying alive was better than the alternative.

In this fourth sense, ordination means to set a Christian believer apart from the “regular people,” and assigning them a rank associated with liturgical functions, by a rite involving the laying-on of hands and prayer, through which an indelible mark is imprinted onto that person’s soul.

Even more narrowly, the notion of the sacramental character is seen as so essential that a person is considered as “not ordained” if they don’t possess that character, which means they never received ordination or the ordination rite was done incorrectly (if the rite was performed by someone incapable of ordaining, or if the ordaining bishop forgot to lay hands on the candidate’s head, for example). The logic here is that a person who does not have the sacramental character lacks the power to offer the sacraments, and therefore cannot be said to possess a “valid ordination.”

We see the logical conclusion of this thinking spelled out in the Catechism of the Council of Trent, Part 2, Chapter 7, Question 30: “The Sacrament of Orders is not to be conferred on very young, or on insane persons, because they do not enjoy the use of reason: if administered, however, it no doubt impresses a character.”

Ludwig Ott states this more clearly in his Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma, telling us on page 460: “The Consecration of a baptised infant as a deacon, priest, or bishop is valid, but not licit.”

In this fifth sense, ordination means to have undergone the ritual of ordination and to have received the sacramental character associated with the rank bestowed by the ritual.

Lastly, there is a competing conception of ordination called the “Cyprianic Doctrine,” which conflates validity with liceity (concepts carefully separated in the above-mentioned “Augustinian Doctrine”). This doctrine teaches that in order for an ordination to be valid, it also has to be “licit,” that means it has to be in conformity with man-made church law and in union with the church institution. Consequently, a person who leaves the Church is considered to lose their confirmation, and a Priest is considered to lose his ordination completely. I mention this in order to make sure the reader is aware it exists, but will not spend too much time on it because 1) literally everybody is illicit in somebody else’s eyes, including the mainstream churches; and 2) this doctrine teaches that “a priest can become a layman,” which Roman Catholic theology has already condemned as heretical in the above-quoted decree from the Council of Trent.

In this sixth and final sense, ordination means not only to have undergone the ritual of ordination, but to remain in good standing and follow the rules of the institution that ordained you!

Yet to throw some more confusion into this discussion, not all ordinations were intended to impose a sacramental character. For example, the Minor Orders and Subdiaconate which existed until Vatican II – and afterward partially reconstituted as “ministries” – were at some points in history considered to bestow a character (The Summa Theologiae claims this for each order), while in later times these were considered not to impart a character at all. For example, in the Appendices we shall see two rites titled “Ordination of an Abbess” (Latin: Ordinatio Abbatissæ), where there is a clear intent to avoid one or more things that could imprint a sacramental character even though one rite explicitly mentions Holy Orders. Likewise, we will also see an example where the exact same wording would (by modern standards) indisputably ordain a man to the diaconate!

Thus for purposes of this article, I’m going to refer to the fifth of these definitions as “sacramental ordination” because of its focus on the character, and also to “non-sacramental ordination” in reference to rites with no intention of imprinting a character. This is roughly parallel to the Eastern Orthodox distinction between “cheirotonia” and “cheirothesia” (to be explained below). This seems like a fair middle ground, while keeping in mind the word’s different uses in ecclesiastical parlance as well as throughout history.

EXPLANATION: CHEIROTONIA AND CHEIROTHESIA

In modern Eastern Orthodox parlance, there are two words for the laying-on of hands: χειροτονία (cheirotonia) and χειροθεσία (cheirothesia). Each signifies differing levels of intention behind placing hands on someone.

Cheirotonia refers exclusively to a laying-on of hands with explicit sacramental intention, i.e., in the ordination of Deacons, Priests, and Bishops.

Cheirothesia refers to laying-on of hands with no sacramental intention, as found in the minor orders such as reader, taper-bearer, and in former times, a (female) Deacon.

Yet even this distinction is not clear, as we have another twist in the narrative. According to OrthodoxWiki, the words “Cheirotonia and cheirothesia formerly were used almost interchangeably, but came to acquire distinct meanings.” And I have not been able to ascertain the exact time when this distinction became clear, whether after the eighth century – as I’ve read from some advocates for women’s ordination – or sometime sooner. Tracking down the date of this distinction is thus on my bucket list and I may update this section in the future.

Now if you think that was confusing, just wait till you see the next section . . .

The Evolving Understanding of Holy Orders

You may have noticed something from the above section, namely that each definition of the word “ordination” came about at a different phase in the Church’s history, and different points in history have seen different interpretations of what makes an ordination valid. This is why any study of women’s ordination rites so complicated, because the insistence on different criteria at different stages of history.

Fortunately, the Holy Ghost once again protects the Church from the speculations of her human members, because the rites for the Major Orders have always contained the laying-on of hands and a prayer with the necessary elements. The problem is that at different times, the Church decided to consider different parts of the rite as necessary for validity. That is to say, the Church’s rites may be stable, but her understanding of “what is required for a valid ordination” has not been static and has actually evolved over the centuries. In fact our current understanding of “essential form” dates to 1947, with a possible slow evolution starting in 1896. Citations will be given below.

Fortunately, this evolution has not been an exercise in drastic changes for the sake of drastic changes, but has effectively been a case of the Church deepening and/or clarifying her understanding of the sacramental principles at work.

According to Leo XIII and Pius XII, the requirements for a valid ordination are 1. the laying-on of hands, and 2. the ordination prayer must invoke the Holy Ghost and also state the reason why the Holy Ghost is being invoked (priesthood, diaconate, etc.).

From about 1200 until 1946, theologians considered the essential act of ordination to be the Tradition of Instruments, by which the ordinand was handed the symbols of the Order being received. We see this stated clearly in Book II, Article 7 of St. Thomas Aquinas’ On the Articles of the Faith and the Sacraments of the Church:

The matter of this sacrament is that matter which is handed over to the candidate at the conferring of the order. Thus, priesthood is conferred by the handing over of the chalice, and so each order is conferred by the handing over of that matter which in a special way pertains to the ministry of that particular order.

Some 150 years after St. Thomas, we find the Council of Florence decreeing the Tradition of Instruments as the essential matter for the sacrament, specifically in the Bull of Union with the Armenians, which tells us the following:

The sixth is the sacrament of orders. Its matter is the object by whose handing over the order is conferred. So the priesthood is bestowed by the handing over of a chalice with wine and a paten with bread; the diaconate by the giving of the book of the gospels; the subdiaconate by the handing over of an empty chalice with an empty paten on it; and similarly for the other orders by allotting things connected with their ministry. The form for a priest is: Receive the power of offering sacrifice in the church for the living and the dead, in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the holy Spirit. The forms for the other orders are contained in full in the Roman pontifical. The ordinary minister of this sacrament is a bishop. The effect is an increase of grace to make the person a suitable minister of Christ.

(Source, emphasis mine)

Yet before this, the same Council in its “Drecree for the Greeks,” indirectly recognized the ordinations of Greek Orthodox, who do not use the Tradition of Instruments. The Council did this by explicitly recognizing their Eucharist: “Also, the body of Christ is truly confected in both unleavened and leavened wheat bread, and priests should confect the body of Christ in either, that is, each priest according to the custom of his western or eastern church.”

This leads us to a riddle about the (perceived) necessity of the Tradition of Instruments, and we may safely say it was only considered a requirement for ordinations within the Roman Church and according to the Roman Rite. In any case this constitutes the only major aberration in either the history or the theology of the Church’s understanding of ordination, as the handing over of a chalice and paten, etc., were absent from the earlier rites and only introduced sometime between the sixth and tenth centuries, depending on which commentator is describing it. However, this was simply added into the rite while the other parts were still retained. The only thing in error was the human understanding of the rite, not the rite itself.

If we return to earlier times, as we’ve seen in the above-cited quote from the Apostolic Tradition, it is clear the Early Church understood ordination to require both the laying-on of hands and prayer: “hands shall not be laid on her … [because] ordination is for the clergy …” This understanding of laying-on of hands can be deduced from Scripture itself, as Acts 6:6 states the Seven Deacons were ordained with prayer and the imposition of hands, and 1 Timothy 4:14 also mentions the grace that is within [Timothy] by prophecy and the laying-on of hands (by the presbyterate!). This verse from 1 Timothy forms yet another scriptural basis for the doctrine of the sacramental character.

We start to see a turning away from the Tradition of Instruments in 1896, when Leo XIII adjudicated the status of Anglican ordinations in Apostolicæ Curæ. In the 24th section of the document, Pope Leo discusses matter and form for the Sacrament of Order, and concludes: “this appears still more clearly in the Sacrament of Order, the ‘matter’ of which, in so far as we have to consider it in this case, is the imposition of hands, which, indeed, by itself signifies nothing definite, and is equally used for several Orders and for Confirmation.”

This clearly led Rome to rethink a few things, because in 1947 Pope Pius XII published Sacramentum Ordinis, which completely reversed the teaching of both St. Thomas and the Council of Florence. He begins by affiriming the principle that “The Church has no power over the substance of the sacraments,” and then addresses the exception that we mentioned in the Council of Florence:

Besides, every one knows that the Roman Church has always held as valid Ordinations conferred according to the Greek rite without the traditio instrumentorum; so that in the very Council of Florence, in which was effected the union of the Greeks with the Roman Church, the Greeks were not required to change their rite of Ordination or to add to it the traditio instrumentorum: and it was the will of the Church that in Rome itself the Greeks should be ordained according to their own rite. It follows that, even according to the mind of the Council of Florence itself, the traditio instrumentorum is not required for the substance and validity of this Sacrament by the will of Our Lord Jesus Christ Himself.

(Section 3)

In a grandiose-sounding sentence in the very next section, Pope Pius declares a return to an earlier understanding of what’s required for an ordination to be valid, and defines the matter for Ordination as the laying on of hands:

Wherefore, after invoking the divine light, We of Our Apostolic Authority and from certain knowledge declare, and as far as may be necessary decree and provide: that the matter, and the only matter, of the Sacred Orders of the Diaconate, the Priesthood, and the Episcopacy is the imposition of hands; and that the form, and the only form, is the words which determine the application of this matter, which univocally signify the sacramental effects – namely the power of Order and the grace of the Holy Spirit – and which are accepted and used by the Church in that sense. It follows as a consequence that We should declare, and in order to remove all controversy and to preclude doubts of conscience, We do by Our Apostolic Authority declare, and if there was ever a lawful disposition to the contrary We now decree that at least in the future the traditio instrumentorum is not necessary for the validity of the Sacred Orders of the Diaconate, the Priesthood, and the Episcopacy.

(Emphasis mine.)

Pius XII would seem to have resolved the issue once and for all, and I agree with his solution. However his wording of “in the future” left an open question as to whether ordinations before 1947 required the Tradition of Instruments. Fortunately for us, that question is outside the scope of this writing (as the Tradition of Implements did not appear until long after the Diaconissate had dissapeared in the West), but it helps to be aware of the various opinions. My own opinion is that the laying-on of hands was always the matter, and that the insistence on the Tradition of Instruments was a gross error.

In the late 1950s, Fr. Emmanuel Doronzo investigated the laying-on of hands versus the Tradition of Instruments in Volume 2 of his Tractatus Dogmaticus de Ordine, devoting 81 pages to analyzing the subject before giving his conclusions. The discussion begins on page 610 and bears the title: “Whether the Matter for Holy Orders is and always was solely the Imposition of Hands and the Form determining it, and whether it is more probable this was instituted by Christ himself.”

Doronzo then walks the reader through his sources, telling us the Tradition of the Instruments in the rite for a Deacon first appears in the Mozarabic Liber Ordinum in the 7th century, then in English Pontificals during the 10th (p. 679); likewise 10th-century England in the rite for a Priest, the Tradition of Paten and Chalice (p. 683).

He announces his conclusion on page 691, stating in no uncertain terms:

Recapitulating what we have said about the historical evolution of the rite of ordination, it is constant that this rite has, from the time of the apostles, essentially consisted of the laying-on of hands and some concomitant prayer, whatever else maybe about the divine origin of this rite, its connection with Moses’ imposition of hands, and its relationship with the rabbinic Semikâh. And the entire ancient tradition of the Fathers has both retained that element, and at no time omitted it, whatever may be said of the silence (easily otherwise explained) of the documents of the 2nd century, and certainly the later practice of the Church expressed expecially in the liturgical books. In this and only this rite, the constant practice of the western and eastern church are in strict agreement.

(Italics and spelling as in original.)

In in other words, the “essential matter” for Holy Orders is and always has been the laying-on of hands, even when the Roman Church said otherwise in regard to the Roman Rite. Case closed, and my poor over-keyboarded fingers are ecstatic that we needn’t belabor this point any further.

Now it’s time for another curve ball.

What is this curve ball, you may ask? It’s the fact that even the modern three-fold system of “Deacon, Priest, and Bishop,” seen as separate Orders, is relatively recent and also dates to Pius XII’s encyclical in 1947. In doing so, he resolved a tension between the offices of priest and bishop that dates back to ancient times. As St. Jerome tells us in his Epistle to Evangelus: “the apostle clearly teaches that presbyters are the same as bishops.”

Later in the same Epistle, he goes on to say:

When subsequently one presbyter was chosen to preside over the rest, this was done to remedy schism and to prevent each individual from rending the church of Christ by drawing it to himself. For even at Alexandria from the time of Mark the Evangelist until the episcopates of Heraclas and Dionysius the presbyters always named as bishop one of their own number chosen by themselves and set in a more exalted position, just as an army elects a general, or as deacons appoint one of themselves whom they know to be diligent and call him archdeacon. For what function, excepting ordination, belongs to a bishop that does not also belong to a presbyter?

About 170 years earlier than Jerome, the Arabic version of the Canons of Hippolytus tells us a priest is ordained the same as a bishop, and the two are the same in all things except for the the ability to ordain and sitting on the throne. The following is from Canon IV:

Now if a Presbyter is ordained, all things are done with him as with a Bishop, except he does not sit on the throne. The same prayer is also said over him as over a Bishop, with the only exception being the title (lit. “name”) of the Episcopate. The Bishop is equal to the presbyter in all things except the throne and ordination, because the power of ordaining is not given him.

(This link contains both the Arabic and a Latin translation. I have translated the above from the Latin.)

This is the seed of how the theology of Holy Orders evolved by the Middle Ages. Namely, medieval theology attempted to reconcile this similarity-yet-difference between Priest and Bishop by considering the Sacrament of Order as “full and perfect in the Priest.” The Episcopate was not considered an order in its own right, but more as a “higher degree” of the priesthood (see Catechism of the Council of Trent, 2:7:25). In practice the Episcopate was a sort of “spiritual expansion pack” that added the power of Ordination, since in the ancient Church the Priest was the ordinary minister of all other Sacraments including Confirmation (in the Eastern Churches, he still is).

This led to other theological questions such as potestas ligata, or whether a priest had the bishop’s sacramental powers “bound up” within him and just needed a special rite to bring them forth; this last is the basis for John Wesley’s ordinations of Methodist clergy in 1784, and for Fr. Pulvermacher’s consecration of Gordon Cardinal Bateman in 1999. Similarly the identification of episcopacy as a degree rather than an order also gave rise to the question of whether per saltum ordination to the Episcopate was actually valid. (Ignoring the fact that St. Matthias’ episcopal ordination in Acts 1:26 could only have happened per saltum!)

In addition to all that, the Minor Orders, Subdiaconate, and Diaconate came to be conceived as lower degrees of the priesthood, which therefore reconciled all the Orders as part and parcel of one sacrament. Yet later – at some time between 1300 and 1947 – the Minor Orders and Sundiaconate came to be seen no longer as part of the Sacrament but as sacramentals that a priest could bestow with the bishop’s permission. As Ludwig Ott explains on page 452 of Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma:

The four Minor Orders and the Subdiaconate are not Sacraments but merely Sacramentals (Sent. Communior.)

The Decretum pro Armenis (D 701) which follows the teaching of St. Thomas and of most of the Schoolmen, cannot be adduced as a decisive counter-proof, as the Decretum is not an infallible doctrinal decision, but merely a practical institution. The Council of Trent took no attitude on the question. The Apostolic Constitution “Sacramentum Ordinis” of Pius XII (1947) obviously favours the view that only the Orders of diaconate, priesthood and episcopate are the stages of sacramental consecration, as only these three are mentioned.

The Minor Orders and the subdiaconate are not of Divine institution, but were only gradually introduced by the Church to meet spiritual requirements. The lectorate is first attested to by Tertullian (De Praescriptione, 41), the subdiaconate by St. Hippolytus of Rome (Apostolic Tradition), all the Minor Orders (which up to the 12th century included the subdiaconate), by Pope St. Cornelius (D 45).

Yet Jerome’s and the Canons’ statements cannot be taken in isolation. Almost 300 years before Jerome and 110 or so years before the Canons, St. Ignatius of Antioch speaks quite differently about Bishops, Priests, and Deacons. In chapter 6 of his Epistle to the Magnesians he says:

… your bishop presides in the place of God, and your presbyters in the place of the assembly of the apostles, along with your deacons, who are most dear to me, and are entrusted with the ministry of Jesus Christ.

Clearly the Bishop is the “top dog” in St. Ignatius’ paradigm and the priests are analogous to the “assembly of the apostles.” He uses a similar analogy in chapter 3 of his Epistle to the Trallians:

In like manner, let all reverence the deacons as an appointment of Jesus Christ, and the bishop as Jesus Christ, who is the Son of the Father, and the presbyters as the sanhedrim of God, and assembly of the apostles. Apart from these, there is no Church.

Ignatius’ high view of the episcopate is probably the clearest in chapters 8 and 9 from his Epistle to the Smyrnæans:

[Chapter 8] See that you all follow the bishop, even as Jesus Christ does the Father, and the presbytery as you would the apostles; and reverence the deacons, as being the institution of God. Let no man do anything connected with the Church without the bishop. Let that be deemed a proper Eucharist, which is [administered] either by the bishop, or by one to whom he has entrusted it. Wherever the bishop shall appear, there let the multitude [of the people] also be; even as, wherever Jesus Christ is, there is the Catholic Church. It is not lawful without the bishop either to baptize or to celebrate a love-feast; but whatsoever he shall approve of, that is also pleasing to God, so that everything that is done may be secure and valid.

[Chapter 9] It is well to reverence both God and the bishop. He who honours the bishop has been honoured by God; he who does anything without the knowledge of the bishop, does [in reality] serve the devil.

In Ignatius one can clearly see the three-fold pattern of Deacon, Priest, and Bishop as clearly separate, as well as the conflating of validity and liceity that we find in Eastern Orthodoxy (as an Orthodox friend summarized it to me in a Facebook conversation recently: “Orthodoxy sees validity as connected to the bishop’s permission”). With Jerome and Augustine, one can more readily trace the trajectory of the Western Church with its conception of Holy Orders and the separation between Power of Orders and Power of Jurisdiction.

In context, Ignatius’ and Jerome’s opinions are products of the Church’s situation in their respective times. Ignatius wrote immediately after the close of the first century, when the Church was small, the Church was illegal, and during a time when Christian communities were small enough that there was no need for anyone other than the Bishop to celebrate the Sacraments. Jerome, on the other hand, was writing toward the dawn of the fifth century; the persecutions were over, Christianity was now the official religion of the Empire, and had grown so large that the Bishop was no longer able to keep up with the people’s sacramental needs all by himself. Even in the Canons of Hippolytus we can see this transition as complete or nigh-complete, indicating the Church’s situation had already changed during the century between St. Ignatius’ martyrdom in 108 and the Canons’ earliest possible date around 225.

So in summary, the Church’s understanding of Holy Orders has developed, progressed, and the Roman Church made one wrong guess over the centuries, which guess was later corrected. We can also see the theology of Holy Orders following two separate yet equally-organic trajectories, one which we can call the “Ignatian-Cyprianic” taking root in the East, and the other “Hieronyman-Augustinian” taking root in the West. This cannot be called a “break” in theology, however, but more like a tree with two stumps growing from the same set of roots. Both trajectories proceed from their starting points along logical and organic lines.

What this means is that as we trace through history and evaluate any given rite, we have to bear in mind that not all people at all times have had the same conception of what makes an ordination an ordination, what distinguishes a sacramental ordination from a non-sacramental one, or even what an ordination actually is.

Yet ultimately we have to pick some sort of a heuristic before we’re able to move forward. Dr. Gary Macy addresses this in his The Hidden History of Women’s Ordination, when talking about the different approaches of theologians and historians:

But to determine one particular definition of ordination as definitive is fundamentally a theological, not an historical, endeavor. Determining what counts as a valid ordination requires that theologians in each Christian denomination decide by what criteria an ordination is considered valid, and further, whether those criteria are eternally valid or mutable over time. Historians do not make such decisions. Historians ask, rather, what ordination meant at a particular moment in the past. Any ceremony called an ordination that fits the criteria established at that time and place was an ordination.

(Emphasis in original)

Dr. Macy’s book contained several “slippery moments” that turned me off, most notably on page 51 where he tells the reader history is a “contemporary construction of more or less plausible scenarios, none of which accurately represents what actually occurred in the past.” However I think his distinction between theological and historical is a valid one, and helps me clarify my interest as exclusively theological. Dr. Macy’s distinction also suggests – correctly, in my opinion – that it’s prudent to approach this subject from three different angles.

Firstly, my criteria for evaluation are those of Pius XII, because 1. it most closely matches the biblical practice of “prayer and the laying-on of hands,” 2. it avoids focusing on culture-specific traits of one or another rite or use, and 3. these two elements have been found in all ordination rites found in the Catholic and Orthodox churches from the earliest recorded documents to the present day.

My second angle is to ask not only “would this rite produce a valid ordination according to the aforementioned criteria,” but also to consider whether the rite would qualify as entrance into a sort of Minor Order. Since the Minor Orders have much broader criteria, this provides us with a stable middle ground.

Lastly, I will also ask the question of “Would this rite have been considered a valid sacramental ordination when it was written?” By approaching from these three angles, we can bring both the theological and the historical to the table.

Alternate Spiritual Currents, Gendered Lineages, and Esoteric Transmission

I owe a debt of gratitude to Jenny Tyson, Bartimaeus Black, and Fr. Kristopher Manghera for helping me work out the thoughts expressed in this section.

Exoteric readers will most likely feel uncomfortable with this section, especially if they’re attached to a triumphalist model of “doing church.” They may be even more put off by my explicit references to occult theory. Yet the existence of alternate currents (lineages) is a part of spiritual reality and therefore must be addressed.

When we talk about “valid ordination,” we typically mean whether a given ordination is valid according to Catholic standards, whatever those standards may be to the person who’s speaking. What a “valid ordination” means in this context is that the recipient has inherited a spiritual lineage, or a “current,” that traces itself back to one or other of the Apostles, and from them to Christ. This is the reason apostolic succession is considered important, because it is the lineage that transmits the spiritual current and by which believers participate in that current’s spiritual power.

What’s not readily understood in these conversations, or even acknowledged, is that while apostolic succession is the only line of transmission documented as coming directly from the Apostles, the fact is that many other lines of spiritual transmission exist “in the wild.”

For example, the Cathars claimed their own form of apostolic succession called an Ordo. Both French and Italian Cathars traced their Ordo from sources either in Bulgaria or a rival “Drugunthian” lineage brought to Europe by a missionary known as “Papa Nicetas.” Both Ordines in turn trace themselves to the founder of the Bogomils (“Pop Bogomil”), and we have no way of knowing for sure whether his lineage was derived from the Apostles, or an earlier sect such as the Euchites, or if he made the whole thing up and an egregore formed from his followers. In any event their ritual for transmitting the lineage, the Consolamentum, would be considered invalid by Catholic standards. But that does not mean it was not valid by their own standards, or that there was no spiritual current transmitted to the next buon’uomo being consoled (or the next buona mugliere!).

The same can be said with lineages from other sources, be they Reiki attunements, Golden Dawn initiations, the Doinel Lineage of French Gnosticism before Jean Bricaud brought the movement into the Vilatte succession, and even the transmission of the “Christmas Eve Prayer” for curing malocchio. And that’s not even close to the tip of the iceberg!

Not only that, some of these lineages are explicitly gendered.

One example of a gendered lineage is the Italian tradition of the Christmas Eve Prayer for curing the Evil Eye. The way I was taught is that only a woman can pass on the power to use that prayer; a man can receive it, he can use it, but he is not able to pass it on. This, then, qualifies as a gendered lineage along female lines.

A parallel example of an gendered lineage would be the Greek method for dealing with the Evil Eye, or the vaskania. The Greek prayer is taught on Good Friday, and can only be passed to a person of the opposite gender. Hence I could not pass it on to another man if I had it, and another man cannot pass it on to me if I don’t have it; I can only receive it from or pass it on to a woman. The transmission can be considered “balanced,” but the lineage definitely has a gendered component.

This brings us to the question of whether Catholic ordination is a gendered lineage, as were most priesthoods in the ancient world (of which the Vestal Virgins are a well-known example).

I am not a fan of Leadbeater, and certainly do not consider his work an authoritative source for theological debates (because clairvoyant insights qualify as either “private revelation” or “unverified personal gnosis,” neither of which anybody is required to believe). However, what he says on this subject may be relevant to our discussion. In his Science of the Sacraments, he tells us the following starting at the bottom of page 349:

It is often asked whether a woman could validly be ordained. That question has practically been answered in an earlier chapter. The forces now arranged for distribution through the priesthood would not work efficiently through a feminine body; but it is quite conceivable that the present arrangements may be altered by the Lord Himself when He comes again into the world. It would no doubt be easy for Him, if He so chose, either to revive some form of the old religions in which the feminine Aspect of the Deity was served by priestesses, or so to modify the physics of the Catholic scheme of forces that a feminine body could be satisfactorily employed in the work. As some of us hold that it will not be long before His advent, the question may be finally settled on unquestionable authority in the near future; but until He comes we have no choice but to administer His Church along the lines laid down for us.

What Leadbeater is claiming is that the “forces now arranged for distribution” constitute a gendered lineage. If this is true, then it would only be possible to impart the sacramental character (of Catholic ordination) onto the soul of a man, in the same sense that it is only possible for a woman to transmit the Christmas Eve Prayer. However, at the end of the day this is still a bald assertion without citations, and I can’t treat it as convincing.

Hence in my mind, the question of whether the “Catholic current” or “Yeshuic lineage” is a gendered lineage remains open. Though if we apply the occult theory of contacts, currents, and egregores, the lineage may have become that way simply by long history of habitual practice. Yet even here I cannot say that as an assertion.

What’s of more interest is the creation of new spiritual lineages, which Leadbeater also discussed in the above quote. This is something more openly discussed in occult theory than in theology.

In occult theory I’ve seen this process referred to as an “esoteric initiation” or “esoteric transmission,” in which the originator of the lineage is either contacted, or makes contact with the source of the lineage’s spiritual current. Theology would refer to this as a “divine commission” such as we saw with Moses or Isaias, and modern scholarship makes references to a “School of Isaias,” i.e. those whom Isaias had commissioned. In fact, once the originator (or originatrix) of the lineage passes it on to a successor, it then becomes an “exoteric lineage” and the beginning of a line of succession.

Another way that new lineages are founded, according to occult theory, is by the formation of egregores, a term that can refer to artificially-created energy pools or sometimes artificial entities that are created and nourished by the thoughts and emotions of the people who create them. In this case the group as a whole becomes the originator of the lineage, which then becomes an “exoteric” lineage as it goes through the process of becoming institutionalized and passed down through the generations.

This is actually an oversimplified definition and a concept foreign to orthodox theology (which relies exclusively on the Spirit Model), yet one I mention because I can’t rule it out. And also because to the best of my knowledge and ability, I try to leave no stone unturned.

Whether through contact or through egregore formation, alternate lineages may be formed, and it is possible for alternate spiritual lineages to have come from Christ himself. This may certainly be the case with any Protestant church that’s been around for enough years, and can be supported by a scriptural basis in Matthew 18:20 with a theological basis in the principle of “extreme economia,” while in occult theory this would line up with the concept of a “contacted lodge.” This would also match up with my experience of “degrees of presence” regarding the Eucharist in non-Catholic churches who neither possess nor care about Catholic notions of apostolic succession.

To put it simply, I would go as far as to speculate that different churches participate in different spiritual lineages, and there may already be functional spiritual lineages derived from Christ that are not dependent on the standard “apostolic succession.” I see no reason why churches who ordain women would be excluded from this possibility, and with enough time it is possible for a female-dominant or even female-only clerical lineage to form. Such may have been the case with the Collyridians in the fourth century, and may be – or may become – the case with present-day groups such as Roman Catholic Womenpriests or the Catholic Mariavite Church.

As with many of my theological meanderings, I again caution the reader that I say all this by way of speculation, not as hard-and-fast assertion.

Let me give a concrete example:

Four years ago (i.e., in 2019), I was approached by two men who had received priestly ordination from the same female bishop. One of them showed me a copy of the rite that was used, and I found the essential form doubtful at best. This means that gender was not a consideration; if the ordinatrix had been male, I would still have had to treat their ordinations as “invalid” insofar as Catholic criteria are concerned. Yet they described things to me about saying Mass that they wouldn’t know if they hadn’t received something. This is what led me to thinking about alternate spiritual currents. It was clear to me that they definitely received some kind of spiritual transmission, just not a big- or small-c catholic ordination.

In fine, my point is that we live in a universe that is very spiritually alive, more alive than the average pew-sitting Christian in the First World might perceive (or be quick to label as “demonic” if they do perceive!). I believe this to be relevant to our inquiry and will connect these dots when we come ot our conclusions. In the meantime, I think it prudent to keep an open view as to whether the “Catholic current” is being transmitted, or another spiritual current might be at play.

Outlier Situations: Women Ordained by Mainstream Bishops

We also need to discuss a phenomenon I refer to as outliers, i.e. individual women who have been ordained, especially to the priesthood and often in secret, either within the Roman Catholic or another church where women’s ordination is not considered “mainstream.” (The only reason I use the term “outlier” is to bring attention to the fact this happens in real life, while keeping it clear that the practice was not normative for the Universal Church at the time it happened.)

The most well-known such ordination is Ludmila Javorová, ordained to the priesthood by Roman Catholic Bishop Felix Maria Davidek on December 29, 1970. He is also reported to have ordained anywhere from four to seven other women to the priesthood, whose names are not publicly known. I say “four to seven women” because different sources give different numbers.

There is a similar and more public story that can’t presently be verified, but one that I’m strongly inclined to believe. The claim is that the first bishops of the Roman Catholic Womenpriests organization were originally consecrated by sympathetic Novus Ordinarian bishops in 2003; their names are kept secret for the time being, and a document bearing those names is said to have been notarized and sealed in a vault. When we remember that the movement’s early ordinations used the 1968 Ordinal “by the book,” and that these are women with advanced theology degrees who knew exactly what they were doing, I find it very easy to believe this story is true.

(Here’s an unrelated note that’s always given me a smile, even when I was still in the Traditional Movement: the RCWP organization calls themselves “Roman Catholic” using logic similar to my former fellow-Sedevacantists. This includes the fact that the known ordinators at the original Danube ceremony were bishops of the Costa-Ferraz lineage, and that the Costa-Ferraz lineage is well-represented within the Traditional Movement too!)

There is, however, one problem with discussing historical outlier ordinations: they were often performed in secret and thus almost impossible to document. We may, however, gain oblique hints from time to time. For example, in 494 Pope Gelasius I wrote a letter to the bishops of Lucana, Calabria, and Sicilia. In chapter 26 of this letter, he furiously tells the bishops he had heard stories of women being entrusted any sort of ministry:

We have impatiently heard of such a disrespect of divine affairs, that women are being confirmed to minister at the sacred altars, and all things appointed to the service of men are given to the employ of a sex which is not capable. Besides which, of all these crimes which we censure one-by-one, all the guilt for these heinous things looks toward the priests, whether those who commit them, or those show themselves to favor their depraved excesses by not publishing the names of the culprits.

(Source: Patrologia Latina, 59:55)

The meaning of this passage has been debated, and I will give two opinions before entering on my own. In 1982, Professor Giorgio Otranto concluded in his article Note sul sacerdozio femminile nell’antichità in margine a una testimonianza di Gelasio I, that Gelasius was referring to women actually being ordained as priests:

I definitively hold that Gelasius, moreso than the exercise of a female diaconal service, sought to stigmatize and condemn an abuse that must have appeared far more grave [to him]: that of true and proper priestesses who carried out all the works reserved solely to the men.

(Original Italian:)

In definitiva ritengo che Gelasio, piuttosto che l’esercizio di un servizio liturgico diaconale femminile, abbia voluto stigmatizzare e condannare un abuso che gli doveva apparire di gran lunga più grave: quello di vere e proprie presbitere che svolgevano tutti i compiti tradizionalmente riservati solo agli uomini.

Otranto further develops this line of thinking by the use of the Pope’s wording and tone suggesting the bishops were actively ordaining women, and correctly notices that Gelasius only cites violations of Church law and tradition without giving a scriptural or theological basis for his condemnations.

Another interpretation is given by Dr. Valerie Karras, who responded to Otranto’s reading of this passage in her 2007 article, Priestesses or Priests’ Wives: Presbytera in Early Christianity:

As for the papal letter, Gelasius never uses any specific clerical titles to describe the women he accuses of taking on liturgical functions. Otranto argues that the way in which Gelasius depicts their actions points to the priesthood, but is unclear 1) whether these women are actually ordained members of the clergy at all; and 2) if ordained, whether they are presbyters or deacons, the latter being a possibility since the word ministrare (“to serve” = Greek diakonein) is used, and since, as Otranto himself notes, southern Italy was strongly Hellenized and thus likely to be familiar with women deacons. In fact, it is entirely possible that the women to whom Gelasius referred were serving at the altar (feminæ sacris altaribus ministrare) either without ordination or as female deacons, since it is unclear what exactly was the nature of their altar ministry.

(Italics in original.)

I’m inclined to agree more with Karras than with Otranto, especially in light of the fact he’s quoting a variant reading of the text. Otranto gives the Latin text as “sacris altaribus ministrare firmentur” (“… are confirmed to minister at the sacred altars”), yet in the PL Migne gives “firmentur” in brackets as an alternate reading, while giving the main text as “sacris altaribus ministrare ferantur” (“… are brought to minister at the sacred altars”). This wording of “brought to the altar” has a weaker meaning than “confirmed at the altar,” and lacks the implication of any kind of rite. In all, we simply don’t know what the Pope heard that prompted him to write these words (or the outrage found in the rest of the letter), nor do we know what really happened.

That said, the level of emotion in the text leads me to think it plausible the Pope may have heard of either an outlier ordination, or at least a rumor of one. The problem is, we have no way of knowing for sure and any hard-and-fast conclusions can only be presumptive at best.

(Later we will come back to Gelasius’ letter, drawing comparisons with similar reports at the Sixth Synod of Paris in the section where we discuss on Local Councils.)

The largest historical outlier, however, may be the Celtic churches, specifically the Insular Celtic churches in Brittania and Hibernia. These churches imported a number of Eastern practices, including the female Diaconate, and there are hints that some form of sacramental women’s ordination may even have been a mainstream occurrence in these lands.

One potential historical example is found in the legend of St. Brigid, the Bethu Brigte, although we do not know if this story is factually true (a valid question with many Saints’ legends). Chapter 19 describes the episcopal consecration of St. Brigid by Bishop Mel:

The bishop being intoxicated with the grace of God there did not recognise what he was reciting from his book, for he consecrated Brigit with the orders of a bishop. ‘This virgin alone in Ireland,’ said Mel, ‘will hold the Episcopal ordination.’ While she was being consecrated a fiery column ascended from her head.

Another account of this incident is found in “On the Life of St. Brigit” in the An Leabhar Breac, a 15th-century manuscript currently housed at the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin. The translation is that of Whitley Stokes, and the entire text can be found at this link:

Brigit, and certain virgins with her, went to Bishop Mél, in Telcha Mide, to take the veil. Glad was he thereat. For humbleness Brigit staid, so that she might be the last to whom the veil should be given. A fiery pillar arose from her head to the ridgepole of the church. Bishop Mél asked: ‘What virgin is there?’ Answered MacCaille: ‘That is Brigit,’ saith he. ‘Come thou, O holy Brigit,’ saith Bishop Mél, ‘that the veil may be sained on thy head before other virgins.’

It came to pass then, through the grace of the Holy Ghost, that the form of ordaining a bishop was read over Brigit. MacCaille said that ‘The order of a bishop should not be (conferred) on a woman.’ Dixit Bishop Mél: ‘No power have I in this matter, inasmuch as by God hath been given unto her this honour beyond every woman.’ Hence, it is that the men of Ireland give the honour of bishop to Brigit’s successor.

These accounts mince no words. The Bishop accidentally read the wrong prayers from his book, and as a result Brigid was consecrated a Bishop in her own right. That a fiery column ascended from her head – again if this story is true – proved to Mel and any onlookers that the ordination was valid.

That “fiery column” makes for another interesting note however, and is open to two equally-probable interpretations. One may interpret this as referring to Brigid’s namesake, the goddess of fire, forge, and hearth. Yet one may also find the column of fire an apt metaphor for the psychic impressions one can receive at Sacred Ordination. Different people describe the experience in different ways, and for example my own experience could be summarized as a “massive opening up.” But this might hint – emphasis on the word might – that the author or compiler of St. Brigid’s legend knew something of the spiritual dynamics at play during sacramental ordinations!

We also possess an anonymous account of Irish Church history written in the 8th century, preserved in Arthur Haddan’s and William Stubbs’ Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents Relating to Great Britain and Ireland. The following On Volume 2, Part 2, page 292. In a marginal note, our editors inform that this section of the chronicle covers the years 440 to 543:

Here begins the Catalogue of the Saints of Ireland, according to diverse times.

The First Order of Catholic Saints was in the time of Patrick. And then they were all bishops, famous and holy and filled with the Holy Ghost, 350 in number, planters of Churches. One was the Head, Christ; and one they had one leader, Patrick; they suffered but one Mass, one celebration, one tonsure from ear to ear. One was the Easter they celebrated, on the fourteenth day of the Moon after the Spring Equinox; and what was excommunicated by one Church, was excommunicated by all. They did not rebuke the administration or consort of women; for being founded upon the rock of Christ, they did not fear the winds of temptation. This Order of the Saints lasted through four kingdoms; this is to say for the time of Læogarius, and Aila Muilt’ and Lugada son of Læogarius, and Tuathail. All these Bishops appeared from the Romans and the Franks and the Britons and the Scots.

(Emphasis added)

The next paragraph of the account continues with the “Second Order,” or “second period,” dating from 543-599 and telling us that by that point, “They rejected the administration of women, separating them from the monasteries.”

This text was quoted in 1885 by James Hastings in his Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, as demonstrating that the Celtic churches ordained women. In Volume 1, page 178, he tells us:

According to primitive Christian custom, no difference was made between man and woman (cf. Gal 3:28), and both were allowed to take part in Church functions. In the monastic houses, moreover, the priestly monks lived together with the priestly nuns, according to an old anonymous reporter, up to the year 543: ‘They did not rebuke the administration or consort of women; for being founded upon the rock of Christ, they did not fear the winds of temptation.’ … At the time, too, when the Irish, with their mission, undertook a forward movement toward Brittany, the Gallican bishops found it especially blameworthy in the incomers that they were accompanied by women, who, like the men, assumed to themselves sacramental functions (cf. the letter of the three bishops in the Revue de Bretagne et de Vendée, 1885, i. p. 5 ff.); they did not know that the Irish-Breton Church had preserved customs and principles of the most ancient Christian Church.

(Italics in original.)

We would do well to turn to this “letter of the three bishops” which Hastings mentions, especially since it speaks to the clash of cultures between the Celtic and Romano-Gallican Churches starting in the early 6th century. Some number of refugees from Brittania came to the Continent in the wake of the Germanic invasions, and the customs they brought with them are criticized in a letter from Bishops Eustochius of Angers, Licinius of Tours, and Melanius of Rennes, addressed to two expatriate Irish Priests named Lovocatus and Catihernus. The relevant text of the letter reads as follows:

To the most blessed lords in Christ, the brother priests Lovocatus and Catihernos. Licinius, Melanius, and Estochius, bishops. It has been brought to our attention by the report of the venerable man, the priest Speratus, that you cease not at carrying [portable] tables through the various hits of your people, and that you presume to celebrate Mass [lit. “to do Mass”] there with women involved in the divine Sacrifice, whom you have named “conhospitæ,” so that while you this distribute the Eucharist, the hold the chalices and presume to administer the Blood of Christ to the people.

We are aggrieved, and not lightly, by the novelty and unheard-of superstition of this thing, for as a horrendous sect which has never been proven to be in Gaul is seeming to emerge in our times, which the Eastern Fathers called “Pepodianism,” after Pepodius the author of this schism, and he presumed to have women associated with himself in the sacrifice; [the Eastern Fathers] commanding that whosoever should desire to belong to this error shall be cast outside the communion of the Church.

On account of which, we believe that in the first place we should admonish your Charity in the love of Christ, for the unity of the Church and the catholic faith, asking that when our letter [lit. “page of letters”] comes to you, you will immediately cease and desist, and make a correction of the aforesaid activities. That is to say from the aforesaid tables, which we do not doubt were consecrated by a priest, and from those women which you call “conhospitæ,” which name is not said or heard without some trembling of the soul, because it is detestable, defaming the clergy and striking shame and horror into holy religion.

According to the rules of the Fathers, we therefore command your charity, that not only should foolish women pollute the divine sacraments by illicit administration, but also that anyone who wishes to live together within the roof of his cell – with the exception of his mother, aunt, sister, or granddaughter – let him be restricted from the threshold of the most holy Church, according to the sentence of the Canons.

There’s a lot to unpack here, and if you’re wondering whether “drama queen mode” was the traditional response when Popes and Bishops heard about a woman being anywhere near an altar, the answer to that question is “Yes.”

In any case, I’ve heard people tell me this text “proves” the Celtic Church ordained women as priests and bishops. Sorry to disappoint, but there’s no “smoking gun” here. The letter is indeed speaking to two customs, both known by the name conhospitæ: one being the “co-ed” religious houses in the Celtic Church, the other being the women who assisted at the altar in a liturgical capacity; the fact these women “confirmed with the chalice,” as our Protestant friends would say, indicates this capacity could’ve ranged anywhere from a sacramental Deaconissate to the status of an “altar girl” in a suburban Novus Ordo parish. In a historical context, the fact that distributing the chalice is the job of a Deacon points toward a sacramental Diaconissate in the Celtic churches, but nothing in the text indicates that any sort of female Presbyterate or Episcopate was in play.

The same can be said about the “administration of women” in the above-quoted chronicle, yet here it can’t be ruled out either. Whether women were ordained to the presbyterate in pre-543 Ireland is something I can’t answer definitively on the basis of the texts under discussion. But if the letter of condemnation is reporting events accurately, I do think there’s enough to form a probable opinion in favor of a sacramental Diaconissate.

Of all these examples, I find the Davidek ordinations the most instructive. His reason for ordaining women to the Presbyterate was the situation of the Czech Church, which at the time was being heavily persecuted by the Cult of Hammer and Sickle. From what my reading has indicated, he expressly ordained them so the sacraments could be brought into women’s prisons and other places where a man could not go without tipping off the authorities. This latter-day example harkens back to the days when the Cæsars decreed Christianity a religio illicita, and Early Christianity was itself a persecuted religion.

Persecution has a way of making people get creative. So I would go as far as to speculate – but not assert – that if individual bishops in the Early Church ordained women to the priesthood, then it may likewise have been as a response to persecution; the bishops in question may have seen no other way to keep the Church alive in their geographical areas and thus opted to play the hand they were dealt. These would still qualify as “outlier” ordinations because they cannot be documented as part of the mainstream tradition, and might also account for the fact most murals alleged to depict ordained women also date from that period in the Church’s history.

My search for documented cases is still ongoing, and I will update this section of the blog post as I find them.

Differing Levels of Intellectual Honesty